Making Reactive-Diffusion Systems Faster, A Deep Dive into Kernel Optimization with Triton

Optimizing Gray-Scott reaction-diffusion simulations using Triton GPU kernels, achieving a 20x speedup through memory optimization and kernel fusion techniques.

Introduction

Efficient simulation and inference on GPUs remain critical bottlenecks in scaling both scientific computing and modern ML systems. Despite the immense raw throughput of today's hardware, naive implementations often fall short due to inefficient memory access patterns, excessive CPU-GPU data transfers, and unbatched kernel execution.

While writing pure CUDA is rewarding and offers full control, it's notoriously difficult to scale cleanly. Ensuring coalesced memory access, managing device memory lifetimes, and scheduling work across SMs is not worth the time investment for every kernel. A more pragmatic approach is to hand-tune only the critical paths, while leveraging higher-level abstractions for everything else.

If you're interested in more of my inference work, including CUDA kernel-level transformer inference optimization with Nsight, I also co-authored this blog with friends. For this post, I walk through my recent experiment of optimizing the Gray-Scott reaction-diffusion simulation using Triton, a high-level GPU programming language developed by OpenAI that's gaining traction in performance-critical ML research.

Starting from a straightforward CPU baseline, I incrementally ported core compute kernels to Triton, aggressively minimized host-device synchronization, and fully redesigned the rendering pipeline for batched GPU execution. The result: a 20x end-to-end speedup, reducing total video generation time from nearly two minutes to under six seconds.

The Gray-Scott Reaction-Diffusion Simulation

I actually chanced upon Gray-Scott reaction-diffusion simulations through a YouTube short video and shortly entered a deep rabbit hole into mathematical biology, differential equations, and WebGL-based demos like this one that let you tweak parameters in real time and watch complexity unfold. Even cooler than playing with the simulator was realizing just how beautiful the underlying mathematics is and how naturally it maps onto the GPU.

At the heart of the Gray-Scott reaction-diffusion model are partial differential equations that describe how two chemical species labeled U and V interact over time and space.

The equations look like this:

Where:

- and are the concentrations of the two chemical species at each spatial location.

- and are diffusion rates for and respectively.

- is the feed rate — how much of chemical is being added into the system.

- is the kill rate — how much of is being removed from the system.

- is the Laplace operator, which computes how values "diffuse" from neighboring points in space.

So why do these equations work great on GPUs? The key lies in the Laplacian approximation, where

The Laplacian approximation looks like this:

That's it. A 5-point stencil. This pattern can be baked into every step of the diffusion simulation to generate beautiful and smooth patterns.

For GPUs, this is gold. Stencil operations are:

- Regular (fixed memory access pattern)

- Dense (no branching)

- Perfectly parallel (each pixel is its own thread)

- And highly optimizable (can leverage shared memory or coalesced loads).

Combining this approximation with the two differential equations given above, we get these practical update functions that we can implement with some kernels!

For information on how these patterns can be modified to generate different behavior, this guide from MIT is pretty good.

The Baseline: Numpy

Oftentimes, when writing GPU kernels to speed up a process, it's good to have a working CPU version to have a baseline that implements all the mathematics properly. Also, I really wanted to see molecules diffusing on my screen!

First, we start with some initial concentrations of U and V. These can really be any shape and are some basic placements like a ring in numpy, so I won't go into the details. Then, for each new frame, we can generate the concentrations with this method.

def laplacian(Z): return ( -4 * Z + np.roll(Z, 1, axis=0) + np.roll(Z, -1, axis=0) + np.roll(Z, 1, axis=1) + np.roll(Z, -1, axis=1) ) def update(U, V): Lu = laplacian(U) Lv = laplacian(V) reaction = U * V * V U += (Du * Lu - reaction + F * (1 - U)) * dt V += (Dv * Lv + reaction - (F + k) * V) * dt np.clip(U, 0, 1, out=U) np.clip(V, 0, 1, out=V) return U, V

To render all the frames and apply a cool cyberpunk style colormaps, we use the following approach:

# cyberpunk colormap colors = [ (0.02, 0.02, 0.1), # Deep, dark blue-black (0.1, 0.0, 0.3), # Dark purple (0.0, 0.2, 0.8), # Electric blue (0.0, 0.8, 0.9), # Bright cyan (0.4, 1.0, 0.6), # Bright green-cyan (1.0, 0.8, 0.0), # Electric yellow (1.0, 0.2, 0.8) # Hot pink ] custom_cmap = LinearSegmentedColormap.from_list("cyberpunk", colors, N=256) # =============FOR EACH IMAGE============== # Use V for visualization img = V.copy() # Check if we have any variation v_min, v_max = V.min(), V.max() if v_max - v_min > 1e-6: img = (img - v_min) / (v_max - v_min) else: # If no variation, try visualizing U instead img = U.copy() u_min, u_max = U.min(), U.max() if u_max - u_min > 1e-6: img = (img - u_min) / (u_max - u_min) else: img = img * 0 # Enhanced contrast and saturation img = img ** 0.5 # Less gamma correction for more vibrant colors # Add a slight contrast boost img = np.clip(img * 1.2 - 0.1, 0, 1) # Convert to color img_color = custom_cmap(img)[..., :3] img_uint8 = (img_color * 255).astype(np.uint8) img_bgr = cv2.cvtColor(img_uint8, cv2.COLOR_RGB2BGR) video.write(img_bgr)

So.... are we done? Well, at this point, I was pretty excited to see some really beautiful videos, but I wasn't so happy that I had to wait 1.5 minutes for a 512x512 resolution video of 5 seconds, and much, much longer for a 1024x1024 resolution video. It was time to bring on the processing power of GPUs to make this a whole lot faster. You will have to read till the end of the article to see the rendering :)

GPU Iteration v0: Convert Laplacian Operation to a CUDA Kernel

In system design, it's often useful to change one component of time to assess its relative importance and easily debug it. To start the transition over to Triton, I decided to tackle the Laplacian function first. For those of you who are unfamiliar with typical workflows involving GPU kernels, here is what it looks like.

- Define the dimensions on which to launch the operation (multiple levels of parallelization, starting with a grid, blocks, then individual threads).

- Allocate buffers for both inputs and outputs on the GPU and copy the necessary data over to the GPU.

- Call kernel, passing in GPU buffers

- Copy data from GPU to CPU

- Use data for the next operations.

Let's look at what these steps look like for the Laplacian kernel.

N = 512 BLOCK_SIZE = 32 grid_x = (N + BLOCK_SIZE - 1) // BLOCK_SIZE grid_y = (N + BLOCK_SIZE - 1) // BLOCK_SIZE grid = (grid_x, grid_y) Z_gpu = Z.cuda() output = torch.zeros_like(Z_gpu)

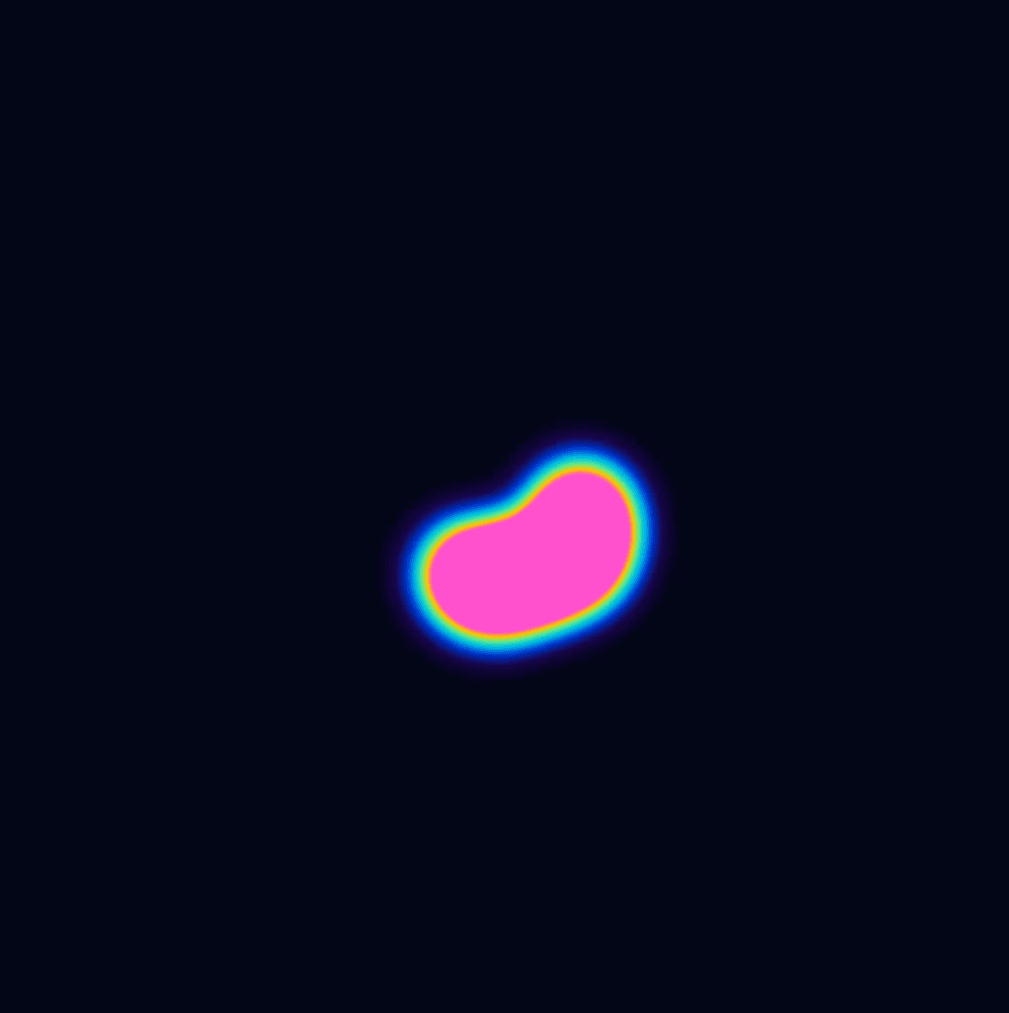

We start by defining a square that is N x N in order to handle a 2D input square like the start position shown in the title image of this article. Then we construct blocks, which are smaller 2D squares that span across this N x N space. The grid dimensions specify the number of blocks on each dimension, and hence, we do a ceiling division to figure out how many blocks we need. After this, we allocate space on the GPU for storing our input Z and our output matrix. Then, on the host end (this is the CPU code that is calling the Python code), we do the following:

laplacian_kernel[grid](Z_gpu, output.cuda(), N, BLOCK_SIZE) Return output.cpu()

Which calls the kernel with the grid we have defined and then moves the output vector back to the CPU for the rest of the code to use. Now let's take a look at the Triton kernel we've defined here as laplacian_kernel.

@triton.jit def laplacian_kernel( input_ptr, output_ptr, N: tl.constexpr, BLOCK_SIZE: tl.constexpr, ): pid_x = tl.program_id(0) pid_y = tl.program_id(1) x_start = pid_x * BLOCK_SIZE y_start = pid_y * BLOCK_SIZE offs_x = tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE) offs_y = tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE) x = x_start + offs_x[:, None] y = y_start + offs_y[None, :] mask = (x > 0) & (x < N - 1) & (y > 0) & (y < N - 1) center_idx = y * N + x left_idx = y * N + (x - 1) right_idx = y * N + (x + 1) up_idx = (y - 1) * N + x down_idx = (y + 1) * N + x center = tl.load(input_ptr + center_idx, mask=mask, other=0) left = tl.load(input_ptr + left_idx, mask=mask, other=0) right = tl.load(input_ptr + right_idx, mask=mask, other=0) up = tl.load(input_ptr + up_idx, mask=mask, other=0) down = tl.load(input_ptr + down_idx, mask=mask, other=0) # Example computation: Laplacian out = -4 * center + left + right + up + down # Store result tl.store(output_ptr + center_idx, out, mask=mask)

It looks a little intimidating at first compared to our 4-line CPU implementation, but let's dissect what is happening here.

pid_x = tl.program_id(0) pid_y = tl.program_id(1) x_start = pid_x * BLOCK_SIZE y_start = pid_y * BLOCK_SIZE

The program_id function tells us which block we are currently looking at on the x and y axes of our 2D grid. In CUDA, the equivalent would be blockIdx.x and blockIdx.y. From this, we can get both the start index within our image. This next part is a little different than CUDA:

offs_x = tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE) offs_y = tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE) x = x_start + offs_x[:, None] y = y_start + offs_y[None, :] mask = (x > 0) & (x < N - 1) & (y > 0) & (y < N - 1)

The arrange method returns a vector of indices of the block (or 0 to 31 in our case). To calculate all the relevant indices for this particular 2D block, we start at the program-specific x_start and y_start indices and add on these vectors. Finally, since we want to only calculate Laplacian values at indices where there are 4 neighbors, we create a mask which is essentially a set of positions that meet a certain condition.

Once we have this mask, we can use Triton operations to perform our stencil operation.

tl.loadto access the current data point and its neighbortl.storeto write the output of the Laplacian stencil back to the output matrix.

After integrating this GPU portion into the existing code, I found that runtime dropped to ~47 seconds, or roughly a 40% reduction in time. While this was exciting, there were some obvious next steps to improve performance.

- For each update step, the data is transferred to the GPU, Laplacian operations are performed, and the data is transferred back to the CPU for the rest of the update step. These memory transfers between the CPU and GPU were highly costly.

- The rest of the update step was on the CPU, which killed performance for the above reason.

def laplacian_gpu_caller(Z): grid_x = (N + BLOCK_SIZE - 1) // BLOCK_SIZE # Ceiling division grid_y = (N + BLOCK_SIZE - 1) // BLOCK_SIZE grid = (grid_x, grid_y) Z_gpu = Z.cuda() output = torch.zeros_like(Z_gpu) laplacian_kernel[grid](Z_gpu, output.cuda(), N, BLOCK_SIZE) return output.cpu() def update(U, V): Lu = laplacian_gpu_caller(U) Lv = laplacian_gpu_caller(V) # THIS SECTION IS ON CPU = BAD! reaction = U * V * V U += (Du * Lu - reaction + F * (1 - U)) * dt V += (Dv * Lv + reaction - (F + k) * V) * dt U = torch.clamp(U, 0, 1) V = torch.clamp(V, 0, 1) return U, V

So the next step was to convert the rest of the update step to a Triton kernel, keeping all operations during the update step within the GPU.

GPU Iteration v1: Moving Entire Update Step to GPU Native Implementation

From the previous step, we already have 2 buffers, Lu and Lv, that have been transferred back to the CPU. Instead, in this iteration, we leave them on the GPU and convert this section to its own GPU kernel:

reaction = U * V * V U += (Du * Lu - reaction + F * (1 - U)) * dt V += (Dv * Lv + reaction - (F + k) * V) * dt U = torch.clamp(U, 0, 1) V = torch.clamp(V, 0, 1)

The dimensions for the grid are the same because the inputs are still our N x N squares. The only new function here is the tl.where function, which is essentially a ternary operator.

@triton.jit def gs_update_kernel( U_ptr, V_ptr, Lu_ptr, Lv_ptr, F, k, dt, Du, Dv, N: tl.constexpr, BLOCK_SIZE: tl.constexpr, ): pid_x = tl.program_id(0) pid_y = tl.program_id(1) x_start = pid_x * BLOCK_SIZE y_start = pid_y * BLOCK_SIZE offs_x = tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE) offs_y = tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE) x = x_start + offs_x[:, None] y = y_start + offs_y[None, :] mask = (x >= 0) & (x <= N-1) & (y >= 0) & (y <= N-1) U = tl.load(U_ptr + y*N + x, mask=mask, other=0) V = tl.load(V_ptr + y*N + x, mask=mask, other=0) Lu = tl.load(Lu_ptr + y*N + x, mask=mask, other=0) Lv = tl.load(Lv_ptr + y*N + x, mask=mask, other=0) reaction = U * V * V updateU = (Du * Lu - reaction + F * (1 - U)) * dt updateV = (Dv * Lv + reaction - (F + k) * V) * dt newU = U + updateU newV = V + updateV # Clip values between 0 and 1 clippedU = tl.where(newU > 1.0, 1.0, tl.where(newU < 0.0, 0.0, newU)) clippedV = tl.where(newV > 1.0, 1.0, tl.where(newV < 0.0, 0.0, newV)) tl.store(U_ptr + y*N + x, clippedU, mask=mask) tl.store(V_ptr + y*N + x, clippedV, mask=mask)

Then we can simplify the update phase to this:

grid_x = (N + BLOCK_SIZE - 1) // BLOCK_SIZE # Ceiling division grid_y = (N + BLOCK_SIZE - 1) // BLOCK_SIZE grid = (grid_x, grid_y) Lu = torch.zeros_like(U) Lv = torch.zeros_like(V) def update(U, V): laplacian_kernel_uv[grid](U, V, Lu, Lv, N, BLOCK_SIZE) gs_update_kernel[grid](U, V, Lu, Lv, F, k, dt, Du, Dv, N, BLOCK_SIZE) return U, V

You can see here that I also fused the U and V updates into a single Triton kernel; however, this change had marginal performance benefits (I will explain why this occurred at a later point in this blog post). Regardless, doing the entire update phase in the GPU and removing intermediary data transfer had a significant effect on performance, bringing the total run time to ~15.5 seconds, close to 6x faster than our base implementation.

Another important step in making these beautiful Gray-Scott renders is the colormapping process, where the intensity of the V chemical species is converted into the beautiful cyberpunk style colors you see in the image at the top. We tackle this next.

GPU Iteration 2: Cybermap Kernel

Who doesn't like to call their kernel "cybermap kernel"? Here is what this mapping process looks like roughly on the CPU.

# Vibrant cyberpunk colormap colors = [ (0.02, 0.02, 0.1), # Deep dark blue-black (0.1, 0.0, 0.3), # Dark purple (0.0, 0.2, 0.8), # Electric blue (0.0, 0.8, 0.9), # Bright cyan (0.4, 1.0, 0.6), # Bright green-cyan (1.0, 0.8, 0.0), # Electric yellow (1.0, 0.2, 0.8) # Hot pink ] custom_cmap = LinearSegmentedColormap.from_list("cyberpunk", colors, N=256) # Enhanced contrast and saturation img = img ** 0.5 # Less gamma correction for more vibrant colors # Add slight contrast boost img = np.clip(img * 1.2 - 0.1, 0, 1) v_min, v_max = np.min(img), np.max(img) if v_max - v_min > 1e-6: img = (img - v_min) / (v_max - v_min) # Convert to color img_color = custom_cmap(img)[..., :3] img_uint8 = (img_color * 255).astype(np.uint8)

As you can see, a linear interpolation is established just once with 256 values and is then used to convert each intensity in img to an RGB value; a highly parallelizable task. We pass this colormap into our GPU kernel as a lookup table and do all contrast boosting and normalization in parallel via a custom kernel. Additionally, we use a technique called batching, which I describe the benefits of below for the unfamiliar:

- Batching reduces overall kernel launches, as one launch can handle multiple images

- Batching allows for more of the GPU to be utilized as we have more data to process at a time, allowing for latency hiding.

- Better memory and compute throughput (which we will see in the next section on analysis).

Now here is the kernel! Note that the grid dimensions are such that the x dimension covers NxN pixels in a 1D arrangement, while the y dimension handles which image in the batch to handle. In other words grid_batched = ((N * N + BLOCK_SIZE - 1) // BLOCK_SIZE, images_per_chunk,). With this lens let's look at the kernel:

@triton.jit def cyberpunk_colormap_kernel( img_ptr, # batch of 10 images of size N * N img_rgb_ptr, # batch of 10 rgb output images of size 3 * N * N torch_colormap_ptr, # cyberpunk style linear interpolation map img_min_ptr, # array of 10 mins img_max_ptr, # array of 10 maxs N: tl.constexpr, BLOCK_SIZE: tl.constexpr ): img_index = tl.program_id(1) img_offset = img_index * N * N rgb_offset = img_offset * 3 offsets = tl.program_id(0) * BLOCK_SIZE + tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE) mask = offsets < N * N # flat index # Reading the minimums for this array img_min = tl.load(img_min_ptr + img_index) img_max = tl.load(img_max_ptr + img_index) val = tl.load(img_ptr + img_offset + offsets, mask=mask, other=0) val = tl.where(img_max - img_min > 1e-6, (val - img_min)/(img_max - img_min), val) val = tl.sqrt(val) val = val * 1.2 - 0.1 val = tl.where(val > 1.0, 1.0, tl.where(val < 0.0, 0.0, val)) idx = (val * 255).to(tl.uint32) base_offset = idx * 3 r = tl.load(torch_colormap_ptr + base_offset + 0, mask=mask) * 255 g = tl.load(torch_colormap_ptr + base_offset + 1, mask=mask) * 255 b = tl.load(torch_colormap_ptr + base_offset + 2, mask=mask) * 255 tl.store(img_rgb_ptr + rgb_offset + offsets * 3 + 0, r.to(tl.uint8), mask=mask) tl.store(img_rgb_ptr + rgb_offset + offsets * 3 + 1, g.to(tl.uint8), mask=mask) tl.store(img_rgb_ptr + rgb_offset + offsets * 3 + 2, b.to(tl.uint8), mask=mask)

I'll leave it to you to explore how this works, but one can see the parallels to the CPU version. The main point of interest is in the indexing calculations, where we find the linear start point for both the input intensity image and output RGB image through these formulas.

img_index = tl.program_id(1) img_offset = img_index * N * N rgb_offset = img_offset * 3 offsets = tl.program_id(0) * BLOCK_SIZE + tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE)

In order to handle this batched approach, we create a GPU buffer that gets updated until it hits its capacity, and then we make a call to this kernel to process the batch.

V_CHUNK_GPU = torch.zeros((images_per_chunk, height, width), dtype=torch.float32, device='cuda')

Here is the sample calling context:

if step % (5*images_per_chunk) == 50: img_min_tensor = torch.tensor([float(v.min()) for v in V_CHUNK_GPU], device="cuda") img_max_tensor = torch.tensor([float(v.max()) for v in V_CHUNK_GPU], device="cuda") for i in range(images_per_chunk): img_batch[i] = V_CHUNK_GPU[i].flatten() cyberpunk_colormap_kernel[grid_batched](img_batch, img_rgb_batch, torch_colormap, img_min_tensor, img_max_tensor, N, BLOCK_SIZE) gpu_frame_chunks.append(img_rgb_batch.clone())

After making these changes, we reduced the runtime from the previous iteration by approximately 3x, bringing the total runtime to around 5.5 seconds! All computational portions of the simulation had been converted over to GPU at this point, and overall performance was much better than our starting point of 88 seconds. It was time to deeply profile kernels and explore next steps.

Analysis and Next Steps

Here is a summary of the average runtime of all the Gray-Scott experiments I worked on. So now, within that final 5.6 seconds of runtime, what is happening? I decided to profile different portions to explore the breakdown of timings.

- 1.99 seconds - calls to

update() - 0.69 seconds - batched handling of

cybermap - 0.68 seconds - maintenance of batched buffer of V species

- 2.17 seconds - CPU-bound video write to file

Just from looking at these timings, we can see that improving the performance of the update function and having better I/O handling for the video write process can still yield additional performance increases. Currently, video write takes place after all frames have been computed, which is a process that can be pipelined with the computational portion. This will be investigated in the future. Additionally, we investigate how optimized these kernels are by exploring an Nsight Compute Report. I found that the documentation for interfacing Triton and Nsight Tooling is somewhat difficult to navigate, so I include this snippet here for how to run Nsight Compute jobs on Triton kernels:

ncu --target-processes all --kernel-name regex:"(cyberpunk_colormap_kernel|gs_update_kernel|laplacian_kernel_uv)" --set full -o triton_kernels_full python3 gs_aws_kernel.py

laplacian_kernel_uv

From this plot, we can see that this kernel lies below the memory roof of the roofline model, indicating that we are heavily memory-bound. A sharp reader will remember that there are duplicate loads happening in the Laplacian kernel that reduce efficiency! For most points, there are 4 neighboring points that need to load that point's value from memory in order to perform the stencil operation. A common technique that is used to resolve that can be applied here to resolve this is the use of shared memory loading. This means that all the threads in a block cooperatively work together to first load a tile of values in one phase, and then move to the compute phase and pull data from this more localized memory instead of pulling from global memory. This reduces duplicate reads from global memory, which is a much more costly process.

Also, we see that the SM busy percentage is quite low at 11.12% due to the small kernel size! We launch one kernel for handling just one image of 512x512. This is a heavy indicator that we should pursue a batched approach to better utilize GPU resources.

Due to inefficient memory access patterns, our warps are often waiting for memory to be available. Of the 4.14 warps we have active per scheduler, on average, only 0.12 warps are available at a given moment, and we only schedule instructions once every 9 cycles, when we can technically schedule instructions every cycle. We want to avoid this! I'll be optimizing this portion in a future post.

gs_update_kernel

Similar to the Laplacian kernel, our gray-scott update kernel faces a very similar problem. It is in a very similar location on the roofline plot, indicating a memory-bound problem. Relative to the memory throughput of 68.22% our compute throughput is only 12.7%. Similar optimizations can be made for this kernel as well.

This point is reinforced here as well. We only schedule instructions every 8.8 cycles and only have 0.18 warps available for the scheduler out of our 5.48 active warps.

Another potential option would be to explore fusing the two kernels. This would greatly reduce the number of global memory accesses, improving throughput. The reason this is possible is that both operations work directly with L and V as inputs. Lu and Lv, which are returned as large matrices, are really just calculating updates for individual locations in the image. Instead of writing to a full output buffer, we can just have thread-local registers that compute the change and add them to L and V.

GPU Iteration???

Looking at these profiling jobs, I decided to try some quick experiments with fusing the Laplace and update steps. To my surprise, I was able to bring the previously 2 seconds of update time down to around 1.1 seconds, bringing the overall runtime to 4.67 seconds! Profiling tools often unveil these little mysteries in potential areas to explore.

Conclusion and Next Steps

This work began as a simple optimization project but quickly evolved into a deep dive through the GPU software stack spanning Triton kernels, memory coalescing, kernel fusion, and roofline analysis. By rewriting core Gray-Scott simulation loops and eliminating redundancy in Laplacian access patterns, I achieved a 19x speedup over the original implementation, while preserving visual fidelity and structure in the reaction-diffusion output.

But this is just the beginning.

In future iterations, I plan to integrate video encoding and simulation directly on-GPU to eliminate host-device transfer bottlenecks, as this remains the largest bottleneck at roughly 2.2 seconds. There's also room to explore shared memory reuse across kernels, persistent blocks, and more sophisticated memory techniques for better cache locality. I'd also like to explore Triton further and try other interesting methods.

This kind of work with tight, high-performance loops and memory-aware design is exactly what excites me. Whether it's for simulation, inference, or interactive systems, I'm drawn to problems where every cycle counts and the architecture demands efficiency.

If you're working on systems that push the boundary of performance in research or industry settings, I'd love to build alongside you. Let's make things that scale with elegance and speed, not just brute force.

Photo Gallery

Code

Repo link will be added soon!